— A Science of Life without Free Will

Notes

Definitions & Implications

how determinism works

- world is deterministic, and we are products of material brains

- biology, environment, interaction = no control

- so we are the cumulative biological & environmental luck

behaviors that makes no sense under determinism

- to not think about something freely

- think of what you’re going to think next

- believe in something you choose to believe

- wish to not wish what we wish for

- will yourself to have more willpower

- moral responsibility for actions

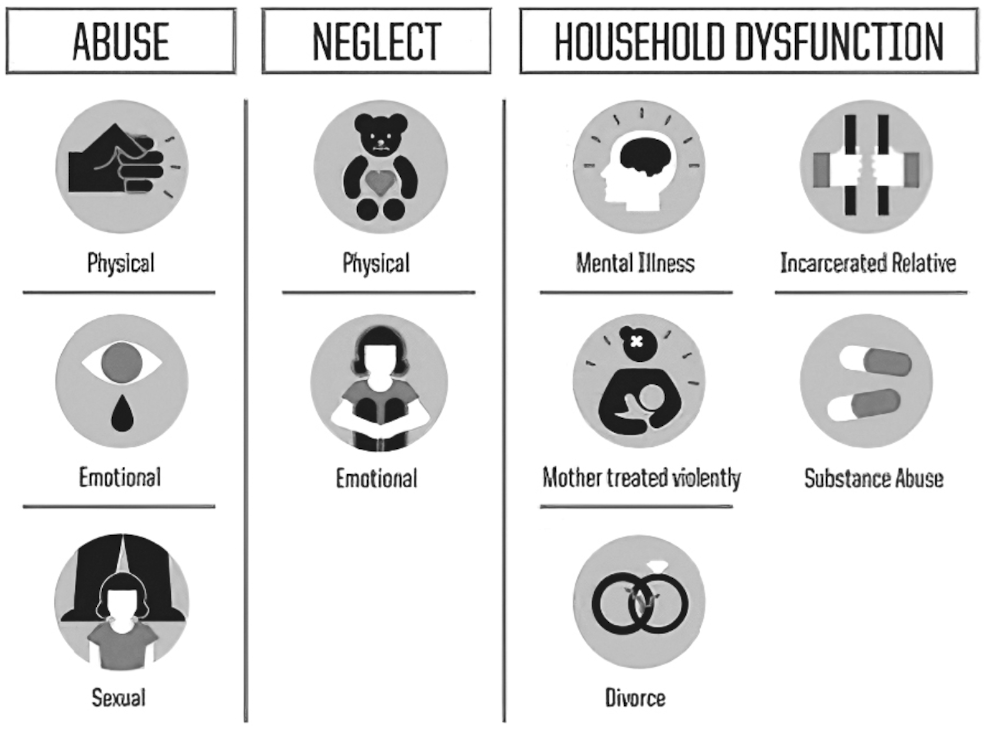

- adverse childhood experience not affecting adult behavior

- executing juvenile murderers

- ignoring dyslexia kids

- blame natural disasters

- praise natural wonders

- blame faulty driving car

- express gratitude because deserve (likely repeat, to inspire others)

- self-congratulate for discipline or kindness

- earned my place

- someone to be entitled to be treated certain ways

- obese because of laziness and not hereditary

- autism because they are cold and weird

justifying blame, punishment, praise, reward

- takes audacity and indifference in light of findings on fetus, ACE…

examples of material brains

- drunk, drugs, exhaustion, frighten

- hormone levels

- chronic stress of unemployment

- ethnically homogeneous neighborhood in teenage

- childhood abuse

- parents values

- Phineas Gage: damaged frontal cortex

- crack baby

- fetus malnourished

- gene variants for dementia, empathy, reactive aggression, anxiety

- attractiveness

- <more below ‘process related to willpower>

examples of material environment - poverty

- racism

- rearing

why believe “free will”

- myopia, narrow focus

- emotional rejection

- the illusion manifests in your consciousness, no alternative route to experiencing otherwise

- wrestled through being challenged by knowledge of biology - worth the time trying to counter their beliefs

problem with myopia

- put all scientific results together → no room for free will

- interlinked, constituting the same ultimate body of knowledge

- neurochemistry

- genetics that specify construction

- evolutionary biology

definition of free will

- a neuron of causeless cause that’s not influenced by

- talk to other neurons

- tired, hungry, stressed, in pain

- sight, sound, smell, touch

- hormones

- lifelong changes regulated by genes cause by

- life-changing events in fetus/childhood/adolescence

- culture, history, ecology

- trade a good and bad person’s genes

- and all of the others’ past

- and they would be switched

- we still congratulate one and despise the other

libet experiment problem

- irrelevance: where did intent come from?

- free to do as intend, but not free to intend what we intend

- sense of intentional movement & actual movement can be seperated

- stimulate decision-making = claim moved without moving

- stimulate pre-SMA, move while claming they hadn’t

One milisecond to one million years

why history matters

- “luck averages out int he long run”

- born into adversity - little compensation, overwhelmingly likely coupled with and followed by more adversity

- good/bad fortune amplified further

seamless turtlism

- every moment - because of what came before it…

- merge all = no crack to slip free will / happen out of thin air

- both statistical and about individuals

brain regions - amygdala

- insula

- visceral disgust = moral disgust (disgusting smell reduces kindness towards lgbt, lying oroally = mouthwash, lying by email = washing hands)

- physical beauty = inner goodness

- don’t distinguished between them

- backwards filling in decision-making insights

- prefrontal cortex

- delayed maturation was selected for, no gene specify what is “right but hard thing”

- evolved to free from genes as much as possible

- childhood adversity matures quicker

- learning new rule, once becomes norm, tasked to other circuits

hormones

- testosterone

- doesn’t cause agression directly

- lowering threshold of preexisting patterns of aggression

- oxytocin

- charitable and trusting to in-group

- more likely to sacrifice out-group

neuroplasticity

- remap of blindfolded auditory / new musical instrument

gut bacteria - apetite, food craving, gene expression of neurons, proclivity towards anxiety, behavioral effect by transplant of bacteria mistaked for FW

childhood

- adverse childhood experience: 1 more score = 35% more adult antisocial, violence, poor cognition, impulse control, substance abuse, teen pregnancy, unsafe sex, depression, poorer health, earlier death

- relative age effect: eleventh months more mature kids snowball peer advantage with more 1-on-1 attention and praise

genes - decide nothing on their own, recipe itself cannot bake cakes

- turned on and off by environment

- different, even opposite effects → can only say what it does in each particular environment

culture - coevolution of gene frequencies, cultural values, practices, reinforcing each other over generations shaping PFC

- chinese rice collectivist region avoid obstacles, wheat individualistic region move obstacles in starbucks

- east asian more dlPFC (emotional regulation, perspective-taking), westerners more vmPFC, insula, anterior cingulate in social processing

- dessert = monotheistic, rainforest = polytheistic

- pastoral “cultures of honor” because herd can be stolen

- extreme but temporary hospitalityto strangers

- adhere to strict codes, sensitive to violation

- insults demand retribution

- warrior classes, valor in battle = high status & glorious afterlife

- crises / natural disasters, high population densities back in 1500 = tight cultures (strictly enforced norms)

country - life expectancy vary by 30 years

- in US, vary by 20 years depending on family

Challenge: Non-biological?

free wont

- separating “us” from “our brain”

- inhibiting behavior circuitry is interchangeable with activating

- “free neuron” that prevents an act equally cannot be found

relevant free will in the past

- “was” was once “now”

dichotomy of biological brain vs “you” sitting in but not of the brain

- neurons, transmitters, receptors… / willpower

- urges / resists acting upon

- naturally higher threshold / fight through pain

- cognitive malfunction / triumph by studying extra hard

- beautiful face / resist concluding entitled to being treated nicely

- conclusion: already good at recognizing left as no control, when infact both no control

processes related to willpower

- cheating

- temptation arises in cheaters = massive activation of PFC = wrestling with whether to cheat

- never cheated: not a stronger PFC to withstand temptation, but no activation, automatic “right thing isnt the harder thing”

- judge

- hunger influences hard processing of parole judgement

- hunger, fatigue, stress, pain… modulate PFC effectiveness

- traumatic brain injury

- half incarcerated for violent antisocial criminality

- avg 8% in general population

- conclusion: grit/squander/discipline/indulgence are all the outcome of brain regions, which is outcome of the seamless 1 sec to 1 M years

Challenge: Chaos?

reductionism

- study complicated things by limiting number of variables considered and adding together (example: gear)

- linear predictability

- has limitations on non-reducible systems

definition

- sensitive to initial state

- no way to predict future state except by marching through simulation of every intervening state (example: rule 22)

- quality: unpredictable

unpredictable ≠ undetermined, determined ≠ determinable

- difference

- predictability: epistemic/what is knowable, say what will happen

- determinism: ontic/what is going on, explain why happened (example: outcome of rule 22 by different people are the same, as there are no causeless causes)

- not epistemically dterministic because perfectly accurate measurement is impossible

- chaotic systems are purely deterministic, just not reductive determinism

cracks left for free will decreases

- cannot predict: is free will

- can predict: stops being free will

- problem: existing only until there is a decrease in our ignorance, “In the face of complicated things, our intuitions beg us to fill up what we don’t understand, even can never understand, with mistaken attributions”

- rate of accuring new neurosience insights is huge, leaving less room

convergence

- different starting states turn produce same outcome

- impossible to know which starting state backwards

- problem: doesnt mean the outome wasnt caused by anything, out of nowhere (no radical eliminative reductionism but not determinism)

Challenge: Emergent Complexity?

definition

- same simple elements together with enough quantity

- spontaneously self-assemble into complex, adaptive global systems, outcome unknown to and not obvious from algorithm of individual agents

- no centralized control/master plan

- irreducible properties exist only on the collective level (example: wetness) and are contained (accurate prediction on collective level without knowing much about component)

- emergent properties are robust and resilient (waterfall over time despite no molecule participates more than once)

- unpredictable + vast difference in the building blocks & ornate, functional outcomes → seemingly defy conventional cause and effect

example

- bees find resouces, comes back to broadcast

- no decision-making bee comparing options

- longer dancing recruits bees → optimal choice emerge implicitly

- tree branches bifurcation

- no specific instruction for each bifurcation

- blueprint as complicated as the structure itself

- neuron networks

- local networks solving familiar problems

- far-flung ones being creative

- keeping down costs of construction & space needed

- no central planning committee

challenge 1: emergence = indeterminism

- problem: unpredictable is not indeterministic

- identical starting state simulations produce same outcome

challenge 2: emergence running wild

- problem: false dichotomy of material brain vs mental state, “I”, emergence ≠ you are out of your brain

- still constrained by what individual agents do (brains are still made of brain cells still function like brain cells)

challenge 3: strong downward causality changing neurons

- there is weak downward causality, examples:

- trigger finger move 1 inch

- private conformity - truly believe (hoppicampus & visual cortex rewrite history of what you saw)

- problem: building blocks dont work differently / acquire complicated properties / once they are part of something emergent

- experience & meaning = emergent, but “not autonomous in the sense of having causal powers that overrise those of their constituents”

Challenge: Quanum Indeterminacy?

problem of magnitude

- quantum states are many many orders of magnitude shorter-lived than anything biologically meaningful (metaphor: movement of glaciers over centuries vs random sneeze)

- law of large numbers + sheer number of quantum events in macro-level objects - decohere & predictable (casino profit “pure chance”)

- non-transferrable quantum qualities to macro world: completely random acts, superimposition, simultaneous y/n, function collapse…

- does not bubble up enough to alter behavior

problem of randomness

- randomness is implausible building clock for free will, and hard for people to actually produce (patterning slips in)

- “whether you believe that free will is compatible with determinism, it isn’t compatible with indeterminism”, “the hypothesis that some of our acts occur freely is not at all the same as the hypothesis that some of our acts occur at random… . How do we get from randomness to rationality?”

problem of “harnessing” randomness

- immune system induce indeterministic randomness, permutation, and filtering/stir up/mess with

- filters are intents that come from turtlism

Moral Implications

moralizing god ≈ free will morality

- large communities → annonymous encounters with strangers

- problems with “religious belief = morality”?

- self-reporting (reputation / socially desireable)

- attributed to wrong cause: not controlled for sex, age, socioecon, marital, sociality stable

- religious people mostly prosocial to themselves

- wrong definition of moral action: prosociality of religious (private, personal, donation) VS prosociality of secular (public service, taxes, civic, duty, equality)

- source of morality: fear of punishment VS human-centered (example: scandanavian, lower religiosity correlates to less corruption/crime/warfare, higher literacy)

death of morality?

- absence of free will ≠ absence of morality

- morality = social construct, independent from scientific aspects of determinism

- running amok: unlikely if educated about roots of behavior, and not that it’s free of consequences (aslo plenty run amok as it is)

- how affect ethical behavior

- free will skeptic & believer: identically honest, generous, resistant to obedience

- in between: less belief in free will = less ethical

- predictor for morality: care about / how they come to stop/start believing in free will, regardless of stance VS nonchalance

Change

already determined, no change?

- we dont change our minds, they are changed by circumstances

- changed by what sources of subsequent change we seek

change occur ≠ free will

- slug: 1 shock = more transmitters, 2 = delayed decomp, 3 = new synapse… entirely mechanistic yet changes adaptively by highly evolved pathways, not freely choosing

- rat: maternal seperation → less conditioning

- human: same transmitters, neural networks with feedback loops highly interconnected, complex

Decrease of Free Will Attribution

subtracting blame

- epilepsy: demonic possesion of freely chosen evil

- seizure near amygdala: aggression

- schizophrenia: mothering VS brain scans

- autism: refridgerator mothers

- sexual orientation

- sexual identity: neurobiology agrees despite genes, gonads, hormones, anatomy, secondaty sexual characteristics

Criminal System

subtract blame ≠ running wild

- broken cars, through no fault of its own, kept off the road

- wild animal, through no fault of its own, barred from your home

- ill person, through no fault of its own, blocked from crowd

- “criminals”, through no fault of their own, quarantined from society

quarantine

- malady thats damaging, dangerous, infectious

- problem in system, not individual (social determinant like poverty, bias, systemic disadvantaging that produce “criminals” are more dangerous)

- protect public till rehabilitate → justify the constraint of their freedom

- constrain minimal amount needed

criticism

- indefinite detention: register when moving, tracking

- precrime apprehension

- preemptive constrain in public health (example: flu, huntington’s disease 50% hereditary, downs syndrome)

- specific: weapon, drug abuse, driving

- actively address all factors: adversity, education, psychological

- in a context of subtracted blame

- constraint compensation becomes motivational

- scandinavian “open prison” less recidivism becuase more return as wage earners

- less per-capita cost: fewer prosoners, smaller police force

joy of punishment

- distal mechanism: beneficial to self-interest in coorperative env

- proximal mechanism: pleasurable (example: paying in currency or effort to watch wrongdoers punished, dopamine)

- decrease

- personal retribution

- third party torture

- hanging

- electrocute

- injection: peaceful

- execution = retraumatizing, impeding recovery for victims, some even actively oppose execution

- government = manifestation of culture values, example: Anders Breivik

- if not dangerous in 21 years, should be released

- staying true to principles, hasnt changed out society

- more humanity but never naivety

- remote student “for our own sake, not for his”

- punishing (vs restaining from further harm) is as immoral as our perception of criminal acts themselves

Psychological Impediments

illusion of sense of agency

- consistently overestimate reliability of random light-switching

- percieved control of button-pushing under transcranial stimulation

- experiment shows independent of size of reward, we prefer exercise more self-discipline (activity in vmPFC) in which rewarding how wisely we think we exercised free agency → mehanistic bio for a belief that it isnt mechanistic

- we cant imagine the subterranean forces of bio history that brought about the choices we didnt freely choose → feeling of free agency

- luxury of deciding effort/self-discipline arent made of biology, surrounded by people who are fortunate enough to feel the same

- overcome intuition is harder when science will never predict precisely outcomes of deterministic yet chaotic systems

illusory free will impacts

- less belief in free will = less intention, invest, effort, error monitoring

- more belief in free will could be damaging: cardiovascular disearse for african american worker

- clinical depression: (learned helplessness) accurate, no overestimate

emotional stance

- death: terror management theory of inevitability, unpredictability of it

- meaninglessness: no crack for purpose, ships never had captains

- fear of truth / deeply held faith misplaced

- fear of it being true because truth could be stressful (1min shock)

- “better off believing in it anyway”

- evolved robust self-deception for survival amid understanding truths about life

- no longer deserve praise for accomplishment / earned or entitled

why it is “freeing” (less biased)

- obesity: self-loathing, bias increase stress disease, not willpower

- massive mis-attribution of choatically determined outcomes to be consequences of different choices

- no justifiable “deserve”, no one more or less worthy

Default mode network

- mind-wandering.

- regulated by the dlPFC

- stimulate dlPFC, you increase activity of the default network

- idle mind = a state that the most superego-ish part of your brain asks for now and then

- take advantage of the creative problem solving that we do when mind-wandering

Select Quotes

1. Turtles All The Way Down

The approach of this book is to show how that determinism works, to explore how the biology over which you had no control, interacting with environment over which you had no control, made you you. – Page 11

we are nothing more or less than the cumulative biological and environmental luck, over which we had no control, that has brought us to any moment. – Page 12

we have no free will at all. Here would be some of the logical implications of that being the case: That there can be no such thing as blame, and that punishment as retribution is indefensible—sure, keep dangerous people from damaging others, but do so as straightforwardly and nonjudgmentally as keeping a car with faulty brakes off the road. That it can be okay to praise someone or express gratitude toward them as an instrumental intervention, to make it likely that they will repeat that behavior in the future, or as an inspiration to others, but never because they deserve it. And that this applies to you when you’ve been smart or self-disciplined or kind. Oh, as long as we’re at it, that you recognize that the experience of love is made of the same building blocks that constitute wildebeests or asteroids. That no one has earned or is entitled to being treated better or worse than anyone else. And that it makes as little sense to hate someone as to hate a tornado because it supposedly decided to level your house, or to love a lilac because it supposedly decided to make a wonderful fragrance. That’s what it means to conclude that there is no free will. – Page 13

We are not machines in most people’s view; as a clear demonstration, when a driver or an automated car makes the same mistake, the former is blamed more.[ – Page 14

we’ll look at the way smart, nuanced thinkers argue for free will, from the perspectives of philosophy, legal thought, psychology, and neuroscience. I’ll be trying to present their views to the best of my ability, and to then explain why I think they are all mistaken. Some of these mistakes arise from the myopia (used in a descriptive rather than judgmental sense) of focusing solely on just one sliver of the biology of behavior. Sometimes this is because of faulty logic, such as concluding that if it’s not possible to ever tell what caused X, maybe nothing caused it. Sometimes the mistakes reflect unawareness or misinterpretation of the science underlying behavior. Most interestingly, I sense that mistakes arise for emotional reasons that reflect that there being no free will is pretty damn unsettling; – Page 14

Yeah, no single result or scientific discipline can do that. But—and this is the incredibly important point—put all the scientific results together, from all the relevant scientific disciplines, and there’s no room for free will.[*] – Page 16

Crucially, all these disciplines collectively negate free will because they are all interlinked, constituting the same ultimate body of knowledge. If you talk about the effects of neurotransmitters on behavior, you are also implicitly talking about the genes that specify the construction of those chemical messengers, and the evolution of those genes—the fields of “neurochemistry,” “genetics,” and “evolutionary biology” can’t be separated. – Page 17

The world is not deterministic; there is free will. These are folks who believe, like I do, that a deterministic world is not compatible with free will—however, no problem, the world isn’t deterministic in their view, opening a door for free-will belief. – Page 19

the absence of clear dichotomies leads to frothy philosophical concepts like partial free will, situational free will, free will in only a subset of us, free will only when it matters or only when it doesn’t. – Page 20

Thus, my stance is that because the world is deterministic, there can’t be free will, and thus holding people morally responsible for their actions is not okay (a conclusion described as “deplorable” by one leading philosopher whose thinking we’re going to dissect big time). – Page 20

Phineas Gage is the textbook case that we are the end products of our material brains. – Page 21

Raise a compatibilist philosopher from birth in a sealed room where they never learn anything about the brain. Then tell them about Phineas Gage and summarize our current knowledge about the frontal cortex. If their immediate response is “Whatever, there’s still free will,” I’m not interested in their views. The compatibilist I have in mind is one who then wonders, “OMG, what if I’m completely wrong about free will?,” ponders hard for hours or decades, and concludes that there’s still free will, here’s why, and it’s okay for society to hold people morally responsible for their actions. – Page 21

What is free will? Groan, we have to start with that, – Page 22

Here’s the challenge to a free willer: Find me the neuron that started this process in this man’s brain, the neuron that had an action potential for no reason, where no neuron spoke to it just before. Then show me that this neuron’s actions were not influenced by whether the man was tired, hungry, stressed, or in pain at the time. That nothing about this neuron’s function was altered by the sights, sounds, smells, and so on, experienced by the man in the previous minutes, nor by the levels of any hormones marinating his brain in the previous hours to days, nor whether he had experienced a life-changing event in recent months or years. And show me that this neuron’s supposedly freely willed functioning wasn’t affected by the man’s genes, or by the lifelong changes in regulation of those genes caused by experiences during his childhood. Nor by levels of hormones he was exposed to as a fetus, when that brain was being constructed. Nor by the centuries of history and ecology that shaped the invention of the culture in which he was raised. Show me a neuron being a causeless cause in this total sense. – Page 23

Trade every factor over which they had no control, and you will switch who would be in the graduation robe and who would be hauling garbage cans. This is what I mean by determinism. And Why Does This Matter? Because we all know that the graduate and the garbage collector would switch places. And because, nevertheless, we rarely reflect on that sort of fact; we congratulate the graduate on all she’s accomplished and move out of the way of the garbage guy without glancing at him. – Page 26

2. The Final Three Minutes Of A Movie

After reviewing these findings, the purpose of this chapter is to show how, nevertheless, all this is ultimately irrelevant to deciding that there’s no free will. This is because this approach misses 99 percent of the story by not asking the key question: And where did that intent come from in the first place? This is so important because, as we will see, while it sure may seem at times that we are free do as we intend, we are never free to intend what we intend. – Page 28

Three Hundred Milliseconds

Now don’t think of Harrison—think about anything else—as we continue recording your EEG. Good, well done. Now don’t think about Harrison, but plan to think about him whenever you want a little while later, and push this button the instant you do. Oh, also, keep an eye on the second hand on this clock and note when you chose to think about Harrison. – Page 29

the sense of intentional movement and actual movement can be separated. Stimulate an additional brain region relevant to decision-making,[*] and people would claim they had just moved voluntarily—without so much as having tensed a muscle. Stimulate the pre-SMA instead, and people would move their finger while claiming that they hadn’t.[ – Page 34

People consistently overestimate how reliably the light occurs, feeling that they control it.[] In another study, subjects believed they were voluntarily choosing which hand to use in pushing a button. Unbeknownst to them, hand choice was being controlled by transcranial magnetic stimulation[] of their motor cortex; nonetheless, subjects perceived themselves as controlling their decisions. – Page 35

Free Won’T: The Power To Veto

“Freedom arises from the creative and indeterministic generation of alternative possibilities, which present themselves to the will for evaluation and selection.” Or in Mele’s words, “even if urges to press are determined by unconscious brain activity, it may be up to the participants whether they act on those urges or not.”[ 30] Thus, “our brains” generate a suggestion, and “we” then judge it; this dualism sets our thinking back centuries. The alternative conclusion is that free won’t is just as suspect as free will, and for the same reasons. Inhibiting a behavior doesn’t have fancier neurobiological properties than activating a behavior, and brain circuitry even uses their components interchangeably. – Page 44

The Death Of Free Will In The Shadow Of Intent

Where does intent come from? Yes, from biology interacting with environment one second before your SMA warmed up. But also from one minute before, one hour, one millennium—this book’s main song and dance. Debating free will can’t start and end with readiness potentials or with what someone was thinking when they committed a crime.[*] – Page 50

This charge of myopia is not meant to sound pejorative. Myopia is central to how we scientists go about finding out new things—by learning more and more about less and less. – Page 51

Dennett is one of the best-known and most influential philosophers out there, a leading compatibilist who has made his case both in technical work within his field and in witty, engaging popular books. He implicitly takes this ahistorical stance and justifies it with a metaphor that comes up frequently in his writing and debates. For example, in Elbow Room: The Varieties of Free Will Worth Wanting, he asks us to imagine a footrace where one person starts off way behind the rest at the starting line. Would this be unfair? “Yes, if the race is a hundred-yard dash.” But it is fair if this is a marathon, because “in a marathon, such a relatively small initial advantage would count for nothing, since one can reliably expect other fortuitous breaks to have even greater effects.” As a succinct summary of this view, he writes, “After all, luck averages out in the long run.”[ 34] No, it doesn’t.[*] Suppose you’re born a crack baby. In order to counterbalance this bad luck, does society rush in to ensure that you’ll be raised in relative affluence and with various therapies to overcome your neurodevelopmental problems? No, you are overwhelmingly likely to be born into poverty and stay there. Well then, says society, at least let’s make sure your mother is loving, is stable, has lots of free time to nurture you with books and museum visits. Yeah, right; as we know, your mother is likely to be drowning in the pathological consequences of her own miserable luck in life, with a good chance of leaving you neglected, abused, shuttled through foster homes. Well, does society at least mobilize then to counterbalance that additional bad luck, ensuring that you live in a safe neighborhood with excellent schools? Nope, your neighborhood is likely to be gang-riddled and your school underfunded. You start out a marathon a few steps back from the rest of the pack in this world of ours. And counter to what Dennett says, a quarter mile in, because you’re still lagging conspicuously at the back of the pack, it’s your ankles that some rogue hyena nips. At the five-mile mark, the rehydration tent is almost out of water and you can get only a few sips of the dregs. By ten miles, you’ve got stomach cramps from the bad water. By twenty miles, your way is blocked by the people who assume the race is done and are sweeping the street. And all the while, you watch the receding backsides of the rest of the runners, each thinking that they’ve earned, they’re entitled to, a decent shot at winning. Luck does not average out over time and, in the words of Levy, “we cannot undo the effects of luck with more luck”; instead our world virtually guarantees that bad and good luck are each amplified further. – Page 51

3. Where Does Intent Come From?

But no matter how fervent, even desperate, you are, you can’t successfully wish to wish for a different intent. And you can’t meta your way out—you can’t successfully wish for the tools (say, more self-discipline) that will make you better at successfully wishing what you wish for. None of us can. – Page 55

turtleism – Page 55

Seconds To Minutes Before

That’s way too little time to have evolved a new brain region to “do” moral disgust. Instead, moral disgust was added to the insula’s portfolio; as it’s said, rather than inventing, evolution tinkers, improvising (elegantly or otherwise) with what’s on hand. Our insula neurons don’t distinguish between disgusting smells and disgusting behaviors, explaining metaphors about moral disgust leaving a bad taste in your mouth, making you queasy, making you want to puke. – Page 57

They won’t explain how a smell confused their insula and made them less of a moral relativist. They’ll claim some recent insight caused them, bogus free will and conscious intent ablaze, to decide that behavior A isn’t okay after all. – Page 58

Jeez, can’t the brain distinguish beauty from goodness? Not especially. – Page 58

Another study showed remarkable somatic specificity, where lying orally (via voice mail) increased the desire for mouthwash, while lying by hand (via email) made hand sanitizers more desirable. One neuroimaging study showed that when lying by voice mail boosts preference for mouthwash, a different part of the sensory cortex activates than when lying by email boosts the appeal of hand sanitizers. Neurons believing, literally, that your mouth or hand, respectively, is dirty. – Page 59

Minutes To Days Before

Well, testosterone causes aggression, so the higher the T level, the more likely you’ll be to make the more aggressive decision.[*] Simple. But as a first complication, T doesn’t actually cause aggression. For starters, T rarely generates new patterns of aggression; instead, it makes preexisting patterns more likely to happen. – Page 61

Oxytocin enhances mother-infant bonding in mammals (and enhances human-dog bonding). – Page 63

As an immensely cool wrinkle, oxytocin doesn’t make us warm and fuzzy and prosocial to everyone. Only to in-group members, people who count as an Us. – Page 64

Weeks To Years Before

Blindfold a volunteer for a week and his auditory projections start colonizing the snoozing visual cortex, enhancing his hearing. – Page 67

there are more bacteria in your gut than cells in your own body,[*] – Page 68

These are mostly subtle effects, but who would have thought that bacteria in your gut were influencing what you mistake for free agency? – Page 68

Back To Adolescence

Thus, delayed maturation isn’t inevitable, given the complexity of frontal construction, where the frontal cortex would develop faster, if only it could. Instead, the delay actively evolved, was selected for. If this is the brain region central to doing the right thing when it’s the harder thing to do, no genes can specify what counts as the right thing. It has to be learned the long, hard way, by experience. – Page 71

This suggests something remarkable—the genetic program of the human brain evolved to free the frontal cortex from genes as much as possible. – Page 71

And Childhood

Thus, essentially every aspect of your childhood—good, bad, or in between—factors over which you had no control, sculpted the adult brain you have while contemplating those buttons. – Page 77

Back To Your Very Beginning: Genes

As it turns out, genes decide nothing, are out at sea. Saying that a gene decides when to generate its associated protein is like saying that the recipe decides when to bake the cake that it codes for. Instead, genes are turned on and off by environment. – Page 80

Back Centuries: The Sort Of People You Come From

As one finding that is beyond cool, Chinese from rice regions accommodate and avoid obstacles (in this case, walking around two chairs experimentally placed to block the way in Starbucks); people from wheat regions remove obstacles (i.e., moving the chairs apart).[ – Page 87

Another literature compares cultures of rain forest versus desert dwellers, where the former tend toward inventing polytheistic religions, the latter, monotheistic ones. This probably reflects ecological influences as well—life in the desert is a furnace-blasted, desiccated singular struggle for survival; rain forests teem with a multitude of species, biasing toward the invention of a multitude of gods. – Page 87

It’s hard to sneak in at night and steal someone’s rice field or rain forest. But you can be a sneaky varmint and rustle someone’s herd, stealing the milk and meat they survive on.[*] This pastoralist vulnerability has generated “cultures of honor” with the following features: (a) extreme but temporary hospitality to the stranger passing through—after all, most pastoralists are wanderers themselves with their animals at some point; (b) adherence to strict codes of behavior, where norm violations are typically interpreted as insulting someone; (c) such insults demanding retributive violence—the world of feuds and vendettas lasting generations; (d) the existence of warrior classes and values where valor in battle produces high status and a glorious afterlife. – Page 88

One last cultural comparison, between “tight” cultures (with numerous and strictly enforced norms of behavior) and “loose” ones. What are some predictors of a society being tight? A history of lots of cultural crises, droughts, famines, and earthquakes, and high rates of infectious diseases.[] And I mean it with “history”—in one study of thirty-three countries, tightness was more likely in cultures that had high population densities back in 1500.[],[ – Page 88

Seamless

In his view, not only does it make no sense to hold us responsible for our actions; we also had no control over the formation of our beliefs about the rightness and consequences of that action or about the availability of alternatives. You can’t successfully believe something different from what you believe.[*] – Page 92

Why did that moment just occur? “Because of what came before it.” Then why did that moment just occur? “Because of what came before that,” forever,[*] isn’t absurd and is, instead, how the universe works. The absurdity amid this seamlessness is to think that we have free will and that it exists because at some point, the state of the world (or of the frontal cortex or neuron or molecule of serotonin …) that “came before that” happened out of thin air. – Page 92

all that came before, with its varying flavors of uncontrollable luck, is what came to constitute you. This is how you became you.[ – Page 93

4. Willing Willpower: The Myth Of Grit

Was-Ness

Agents become responsible for their dispositions and values in the course of normal life, even when these dispositions and values are the product of awful constitutive luck. At some point bad constitutive luck ceases to excuse, because agents have had time to take responsibility for it.[ – Page 97

Whether that free will was-ness was a slow maturational process or occurred in a flash of crisis or propitiousness, the problem should be obvious. Was was once now. – Page 99

What You Were Given And What You Do With It

Major underachievers that can resist anything except temptation. We are replete with human examples, always featuring the word squander. – Page 101

Psychologist James Cantor of the University of Toronto reviewed the neurobiology of pedophilia. The wrong mix of genes, endocrine abnormalities in fetal life, and childhood head injury all increase the likelihood. Does this raise the possibility that a neurobiological die is cast, that some people are destined to be this way? Precisely. Cantor concludes correctly, “One cannot choose to not be a pedophile.” But then he does an Olympian leap across the Grand Canyon–size false dichotomy of compatibilism. Does any of that biology lessen the condemnation and punishment that Sandusky deserved? No. “One cannot choose to not be a pedophile, but one can choose to not be a child molester” (my emphasis).[ – Page 103

And then on the right is the free will you supposedly exercise in choosing what you do with your biological attributes, the you who sits in a bunker in your brain but not of your brain. Your you-ness is made of nanochips, old vacuum tubes, ancient parchments with transcripts of Sunday-morning sermons, stalactites of your mother’s admonishing voice, streaks of brimstone, rivets made out of gumption. Whatever that real you is composed of, it sure ain’t squishy biological brain yuck. When viewed as evidence of free will, the right side of the chart is a compatibilist playground of blame and praise. It seems so hard, so counterintuitive, to think that willpower is made of neurons, neurotransmitters, receptors, and so on. There seems a much easier answer—willpower is what happens when that nonbiological essence of you is bespangled with fairy dust. And as one of the most important points of this book, we have as little control over the right side of the chart as over the left. Both sides are equally the outcome of uncontrollable biology interacting with uncontrollable environment. – Page 104

The Cognitive Pfc

Once that novel rule persists and has stopped being novel, it becomes the task of other, more automatic brain circuitry. Few of us need to activate the PFC to pee nowhere but in the bathroom; but we sure did when we were three. – Page 107

The Social Pfc

What happens in the brains of cheaters when temptation arises? Massive activation of the PFC, the neural equivalent of the person wrestling with whether to cheat.[ 16] And then for the profound additional finding. What about the people who never cheated—how do they do it? Maybe their astonishingly strong PFC pins Satan to the mat each time. Major willpower. But that’s not what happens. In those folks, the PFC doesn’t stir. At some point after “don’t pee in your pants” no longer required the PFC to flex its muscles, an equivalent happened in such individuals, generating an automatic “I don’t cheat.” As framed by Greene, rather than withstanding the siren call of sin thanks to “will,” this instead represents a state of “grace.” Doing the right thing isn’t the harder thing. – Page 109

The Legacy Of The Preceding Seconds To An Hour

Thus, all sorts of things often out of your control—stress, pain, hunger, fatigue, whose sweat you’re smelling, who’s in your peripheral vision—can modulate how effectively your PFC does its job. – Page 120

The Legacy Of The Preceding Days To Years

Roughly half the people incarcerated for violent antisocial criminality have a history of TBI, versus about 8 percent of the general population; having had a TBI increases the likelihood of recidivism in prison populations. – Page 123

To summarize this section, when you try to do the harder thing that’s better, the PFC you’re working with is going to be displaying the consequences of whatever the previous years have handed you. – Page 124

Further Back

An ACE score, a fetal adversity score, last chapter’s Ridiculously Lucky Childhood Experience score—they all tell the same thing. It takes a certain kind of audacity and indifference to look at findings like these and still insist that how readily someone does the harder things in life justifies blame, punishment, praise, or reward. – Page 129

The Legacy Of The Genes You Were Handed, And Their Evolution

A crucial point about genes related to brain function (well, pretty much all genes) is that the same gene variant will work differently, sometimes even dramatically differently, in different environments. This interaction between gene variant and variation in environment means that, ultimately, you can’t say what a gene “does,” only what it does in each particular environment in which it has been studied. – Page 130

The Cultural Legacy Bequeathed To Your Pfc By Your Ancestors

A meta-analysis of thirty-five studies neuroimaging subjects during social-processing tasks showed that East Asians average higher activity in the dlPFC than Westerners (along with activation of a brain region called the temporoparietal junction, which is central to theory of mind); this is basically a brain more actively working on emotion regulation and understanding other people’s perspectives. In contrast, Westerners present a picture of more emotional intensity, self-reference, capacity for strongly emotional disgust or empathy—higher levels of activity in the vmPFC, insula, and anterior cingulate. – Page 133

there’s coevolution of gene frequencies, cultural values, child development practices, reinforcing each other over the generations, shaping what your PFC is going to be like. – Page 134

The Death Of The Myth Of Freely Chosen Grit

We’re pretty good at recognizing that we have no control over the attributes that life has gifted or cursed us with. But what we do with those attributes at right/ wrong crossroads powerfully, toxically invites us to conclude, with the strongest of intuitions, that we are seeing free will in action. But the reality is that whether you display admirable gumption, squander opportunity in a murk of self-indulgence, majestically stare down temptation or belly flop into it, these are all the outcome of the functioning of the PFC and the brain regions it connects to. And that PFC functioning is the outcome of the second before, minutes before, millennia before. The same punch line as in the previous chapter concerning the entire brain. And invoking the same critical word—seamless. – Page 134

In this setting, the vmPFC is coding for how much we prefer circumstances that reward self-discipline. Thus, this is the part of the brain that codes for how wisely we think we’ll be exercising free will. In other words, this is the nuts-and-bolts biological machinery coding for a belief that there are no nuts or bolts.[ 59] Sam Harris argues convincingly that it’s impossible to successfully think of what you’re going to think next. The takeaway from chapters 2 and 3 is that it’s impossible to successfully wish what you’re going to wish for. This chapter’s punchline is that it’s impossible to successfully will yourself to have more willpower. And that it isn’t a great idea to run the world on the belief that people can and should. – Page 135

5. A Primer On Chaos

These are subjects that fundamentally upend how we think about how complex things work. But nonetheless, they are not where free will dwells. – Page 139

Chaoticism You Can Do At Home

What is chaotic about rule 22? We’ve now seen that, depending on the starting state, by applying rule 22 you can get one of three mature patterns: (a) nothing, because it went extinct; (b) a crystallized, boring, inorganic periodic pattern; (c) a pattern that grows and writhes and changes, with pockets of structure giving way to anything but, a dynamic, organic profile. And as the crucial point, there is no way to take any irregular starting state and predict what row 100, or row 1,000, or row any-big-number will look like. You have to march through every intervening row, simulating it, to find out. – Page 153

6. Is Your Free Will Chaotic?

The Age Of Chaos

The more fundamental reason for chaoticism getting off to a slow start was that if you have a reductive mindset, unsolvable, nonlinear interactions among a large number of variables is a total pain to study. Thus, most researchers tried to study complicated things by limiting the number of variables considered so that things remained tame and tractable. And this guaranteed the incorrect conclusion that the world is mostly about linear, additive predictability and nonlinear chaoticism was a weird anomaly that could mostly be ignored. – Page 157

Wrong Conclusion #1: The Freely Choosing Cloud

brouhaha – Page 161

determinism and predictability are very different things. Even if chaoticism is unpredictable, it is still deterministic. The difference can be framed a lot of ways. One is that determinism allows you to explain why something happened, whereas predictability allows you to say what happens next. Another way is the woolly-haired contrast between ontology and epistemology; the former is about what is going on, an issue of determinism, while the latter is about what is knowable, an issue of predictability. Another is the difference between “determined” and “determinable” (giving rise to the heavy-duty title of one heavy-duty paper, “Determinism Is Ontic, Determinability Is Epistemic,” by philosopher Harald Atmanspacher).[ 9] Experts tear their hair out over how fans of “chaoticism = free will” fail to make these distinctions. “There is a persistent confusion about determinism and predictability,” write physicists Sergio Caprara and Angelo Vulpiani. The first name–less philosopher G. M. K. Hunt of the University of Warwick writes, “In a world where perfectly accurate measurement is impossible, classical physical determinism does not entail epistemic determinism.” The same thought comes from philosopher Mark Stone: “Chaotic systems, even though they are deterministic, are not predictable [they are not epistemically deterministic]… . To say that chaotic systems are unpredictable is not to say that science cannot explain them.” – Page 161

Row eleventy-three would not be what it is because at row eleventy-two, you or the dolphin just happened to choose to let the open-or-filled split in the road depend on the spirit moving you or on what you think Greta Thunberg would do. That pattern was the outcome of a completely deterministic system consisting of the eight instructions comprising rule 22. At none of the 100,000 junctures could a different outcome have resulted (unless a random mistake occurred; as we’ll see in chapter 10, constructing an edifice of free will on random hiccups is quite iffy). Just as the search for an uncaused neuron will prove fruitless, likewise for an uncaused box. – Page 162

Back to the 1922 cohort. The person in question has started shoplifting, threatening strangers, urinating in public. Why did he behave that way? Because he chose to do so. Year 2022’ s cohort, same unacceptable acts. Why will he have behaved that way? Because of a deterministic mutation in one gene.[*] – Page 163

“free will” is what we call the biology that we don’t understand on a predictive level yet, and when we do understand it, it stops being free will. Not that it stops being mistaken for free will. It literally stops being. There is something wrong if an instance of free will exists only until there is a decrease in our ignorance. – Page 163

We do something, carry out a behavior, and we feel like we’ve chosen, that there is a Me inside separate from all those neurons, that agency and volition dwell there. Our intuitions scream this, because we don’t know about, can’t imagine, the subterranean forces of our biological history that brought it about. It is a huge challenge to overcome those intuitions when you still have to wait for science to be able to predict that behavior precisely. But the temptation to equate chaoticism with free will shows just how much harder it is to overcome those intuitions when science will never be able to predict precisely the outcomes of a deterministic system. – Page 164

Wrong Conclusion #2: A Causeless Fire

So you can’t do radical eliminative reductionism and decide what single thing caused the fire, which button presser delivered the poison, or what prior state gave rise to a particular chaotic pattern. But that doesn’t mean that the fire wasn’t actually caused by anything, that no one shot the bullet-riddled prisoner, or that the chaotic state just popped up out of nowhere. Ruling out radical eliminative reductionism doesn’t prove indeterminism. Obviously. – Page 166

Conclusion

In the face of complicated things, our intuitions beg us to fill up what we don’t understand, even can never understand, with mistaken attributions. – Page 167

7. A Primer On Emergent Complexity

Unpredictable is not the same thing as undetermined; reductive determinism is not the only kind of determinism; chaotic systems are purely deterministic, shutting down that particular angle of proclaiming the existence of free will. – Page 168

The amazingness is not that, wow, something as complicated as Versailles can be built out of simple bricks.[] It’s that once you made a big enough pile of bricks, all those witless little building blocks, operating with a few simple rules, without a human in sight, assembled themselves into Versailles. This is not chaos’s sensitive dependence on initial conditions, where these identical building blocks actually all differed when viewed at a high magnification, and you then butterflew to Versailles. Instead, put enough of the same simple elements together, and they spontaneously self-assemble into something flabbergastingly complex, ornate, adaptive, functional, and cool. With enough quantity, extraordinary quality just … emerges, often even unpredictably.[],[ 1] As it turns out, such emergent complexity occurs in realms very pertinent to our interests. The vast difference between the pile of gormless, identical building blocks and the Versailles they turned themselves into seems to defy conventional cause and effect. Our sensible sides think (incorrectly …) of words like indeterministic. Our less rational sides think of words like magic. In either case, the “self” part of self-assembly seems so agentive, so rife with “be the palace of bricks that you wish to be,” that dreams of free will beckon. – Page 169

Why We’Re Not Talking About Michael Jackson Moonwalking

There are all these interchangeable, fungible marching band marchers with the same minuscule repertoire of movements. Why doesn’t this count as emergence? Because there’s a master plan. – Page 170

—Out of the hugely complicated phenomena this can produce emerge irreducible properties that exist only on the collective level (e.g., a single molecule of water cannot be wet; “wetness” emerges only from the collectivity of water molecules, and studying single water molecules can’t predict much about wetness) and that are self-contained at their level of complexity (i.e., you can make accurate predictions about the behavior of the collective level without knowing much about the component parts). As summarized by Nobel laureate physicist Philip Anderson, “More is different.”[*],[ 3]—These emergent properties are robust and resilient—a waterfall, for example, maintains consistent emergent features over time despite the fact that no water molecule participates in waterfall-ness more than once.[ – Page 171

But take the roughly ten thousand ants in a typical colony, set them loose on the eight-feeding-site version, and they’ll come up with something close to the optimal solution out of the 5,040 possibilities in a fraction of the time it would take you to brute-force it, with no ant knowing anything more than the path that it took plus two rules (which we’ll get to). This works so well that computer scientists can solve problems like this with “virtual ants,” making use of what is now known as swarm intelligence.[*],[ – Page 172

Informative Scouts Followed By Random Encounters

Note—there is no decision-making bee that gets information about both sites, compares the two options, picks the better one, and leads everyone to it. Instead, longer dancing recruits bees that will dance longer, and the comparison and optimal choice emerge implicitly; this is the essence of swarm intelligence.[ – Page 174

Here’s the thing that makes the audience shout for more—the wall outlines the coastline around Tokyo; the slime was plopped onto where Tokyo would be, and the oat flakes corresponded to the suburban train stations situated around Tokyo. And out of the slime mold emerged a pattern of tubule linkages that was statistically similar to the actual train lines linking those stations. – Page 178

Fitting Infinitely Large Things Into Infinitely Small Spaces

How are bifurcating structures like these generated in biological systems, on scales ranging from a single cell to a massive tree? Well, I’ll tell you one way it doesn’t happen, which is to have specific instructions for each bifurcation. – Page 188

Let’S Design A Town

Get the correct ratio of places for sinning—a gelato shop, a bar—to those for repenting—a fitness center, a church. – Page 195

Talk Locally, But Don’T Forget To Also Talk Globally Now And Then

While you can’t optimize more than one attribute, you can optimize how differing demands are balanced, what trade-offs are made, to come up with the network that is ideal for the balance between predictability and novelty in a particular environment.[*] – Page 203

Thus, on scales ranging from single neurons to far-flung networks, brains have evolved patterns that balance local networks solving familiar problems with far-flung ones being creative, all the while keeping down the costs of construction and the space needed. And, as usual, without a central planning committee.[*],[ – Page 203

Emergence Deluxe

many more.[*],[ – Page 204

A random bunch of neurons, perfect strangers floating in a beaker, spontaneously build themselves into the starts of our brains.[*] Self-organized Versailles is child’s play in comparison.[ – Page 206

8. Does Your Free Will Just Emerge?

First, What All Of Us Can Agree On

So these free-will believers accept that an individual neuron cannot defy the physical universe and have free will. But a bunch of them can; to quote List, “free will and its prerequisites are emergent, higher-level phenomena.”[ 2] Thus, a lot of people have linked emergence and free will; I will not consider most of them because, to be frank, I can’t understand what they’re suggesting, and to be franker, I don’t think the lack of comprehension is entirely my fault. – Page 208

Problem #2: Orphans Running Wild

The next mistake is a broader one—the idea that emergence means the reductive bricks that you start with can give rise to emergent states that can then do whatever the hell they want. This has been stated in a variety of ways, where terms like brain, cause and effect, or materialism stand in for the reductive level, while terms like mental states, a person, or I imply the big, emergent end product. – Page 213

Problem #3: Defying Gravity

A 2005 study concerning social conformity shows a particularly stark, fascinating version of the emergent level manipulating the reductive business of individual neurons. Sit a subject down and show them three parallel lines, one clearly shorter than the other two. Which is shorter? Obviously that one. But put them in a group where everyone else (secretly working on the experiment) says the longest line is actually the shortest—depending on the context, a shocking percentage of people will eventually say, yeah, that long line is the shortest one. This conformity comes in two types. In the first, go-along-to-get-along public conformity, you know which line is shortest but join in with everyone else to be agreeable. In this circumstance, there is activation of the amygdala, reflecting the anxiety driving you to go along with what you know is the wrong answer. The second type is “private conformity,” where you drink the Kool-Aid and truly believe that somehow, weirdly, you got it all wrong with those lines and everyone else really was correct. And in this case, there is also activation of the hippocampus, with its central role in learning and memory—conformity trying to rewrite the history of what you saw. But even more interesting, there’s activation of the visual cortex—“ Hey, you neurons over there, the line you foolishly thought was longer at first is actually shorter. Can’t you just see the truth now?”[*],[ – Page 215

So some emergent states have downward causality, which is to say that they can alter reductive function and convince a neuron that long is short and war is peace. The mistake is the belief that once an ant joins a thousand others in figuring out an optimal foraging path, downward causality causes it to suddenly gain the ability to speak French. – Page 216

That the building blocks work differently once they’re part of something emergent. It’s like believing that when you put lots of water molecules together, the resulting wetness causes each molecule to switch from being made of two hydrogens and one oxygen to two oxygens and one hydrogen. But the whole point of emergence, the basis of its amazingness, is that those idiotically simple little building blocks that only know a few rules about interacting with their immediate neighbors remain precisely as idiotically simple when their building-block collective is outperforming urban planners with business cards. Downward causation doesn’t cause individual building blocks to acquire complicated skills; instead, it determines the contexts in which the blocks are doing their idiotically simple things. – Page 217

It is the assumption that emergent systems “have base elements that behave in novel ways when they operate as part of the higher-order system.” But no matter how unpredicted an emergent property in the brain might be, neurons are not freed of their histories once they join the complexity.[ – Page 217

“while the capacities for experience and meaning are emergent properties of biophysical systems, the capacity for behavioral regulation is not. The capacity for self-regulation is an already existing capacity of living systems.” There’s still gravity.[ – Page 218

9. A Primer On Quantum Indeterminacy

Low-Rent Randomness: Brownian Motion

Mind you, this isn’t the unpredictability of cellular automata, where every step is deterministic but not determinable. Instead, the state of a particle in any given instant is not dependent on its state an instant before. Laplace is vibrating disconsolately in his grave. – Page 222

Wave/Particle Duality

(To jump ahead for a moment, you can guess that things are going to get very New Agey if you assume that the macroscopic world—big things like, say, you—also works this way. You can be in multiple places at once; you are nothing but potential. Merely observing something can change it;[*] your mind can alter the reality around it. Your mind can determine your future. Heck, your mind can change your past. More jabberwocky to come.) – Page 227

10. Is Your Free Will Random?

Quantum Orgasmic-Ness: Attention And Intention Are The Mechanics Of Manifestation

Some problems here are obvious. These papers, which are typically unvetted and unread by neuroscientists, are published in journals that scientific indexes won’t classify as scientific journals (e.g., NeuroQuantology) and are written by people not professionally trained to know how the brain works.[ – Page 233

Problem #1: Bubbling Up

This strikes me as akin to hypothesizing that the knowledge contained in a library emanates not from the books but from the little carts used to transport books around for reshelving.[ – Page 236

MIT physicist Max Tegmark showed that the time course of quantum states in microtubules is many, many orders of magnitude shorter-lived than anything biologically meaningful; in terms of the discrepancy in scale, Hameroff and Penrose are suggesting that the movement of a glacier over the course of a century could be significantly influenced by random sneezes among nearby villagers. – Page 236

“The law of large numbers, combined with the sheer number of quantum events occurring in any macro-level object, assure us that the effects of random quantum-level fluctuations are entirely predictable at the macro level, much the way that the profits of casinos are predictable, even though based on millions of ‘purely chance’ events.” – Page 238

Neuronal Spontaneity

Background noise. Interesting term. In other words, when you’re just lying there, doing nothing, there’s all sorts of random burbling going on throughout the brain, once again begging for an indeterminacy interpretation. Until some mavericks, principally Marcus Raichle of Washington University School of Medicine, decided to study the boring background noise. Which, of course, turns out to be anything but that—there’s no such thing as the brain doing “nothing”—and is now known as the “default mode network.” And, no surprise by now, it has its own underlying mechanisms, is subject to all sorts of regulation, serves a purpose. One such purpose is really interesting because of its counterintuitive punch line. Ask subjects in a brain scanner what they were thinking at a particular moment, and the default network is very active when they are daydreaming, aka “mind-wandering.” The network is most heavily regulated by the dlPFC. The obvious prediction now would be that the uptight dlPFC inhibits the default network, gets you back to work when you’re spacing out thinking about your next vacation. Instead, if you stimulate someone’s dlPFC, you increase activity of the default network. An idle mind isn’t the Devil’s playground. It’s a state that the most superego-ish part of your brain asks for now and then. Why? Speculation is that it’s to take advantage of the creative problem solving that we do when mind-wandering.[ – Page 244

Problem #2: Is Your Free Will A Smear?

Suppose the functioning of every part of your brain as well as your behavior could most effectively be understood on the quantum level. It’s difficult to imagine what that would look like. Would we each be a cloud of superimposition, believing in fifty mutually contradictory moral systems at the same time? Would we simultaneously pull the trigger and not pull the trigger during the liquor store stickup, and only when the police arrive would the macro-wave function collapse and the clerk be either dead or not? – Page 246

Or as often pointed out by Sam Harris, if quantum mechanics actually played a role in supposed free will, “every thought and action would seem to merit the statement ‘I don’t know what came over me.’ ” Except, I’d add, you wouldn’t actually be able to make that statement, since you’d just be making gargly sounds because the muscles in your tongue would be doing all sorts of random things. As emphasized by Michael Shadlen and Adina Roskies, whether you believe that free will is compatible with determinism, it isn’t compatible with indeterminism.[*] Or in the really elegant words of one philosopher, “Chance is as relentless as necessity.”[ – Page 247

Problem #3: Harnessing The Randomness Of Quantum Indeterminacy To Direct The Consistencies Of Who We Are

As such, this is a three-step process. One—the immune system determines it’s time to induce some indeterministic randomness. Two—the random gene shuffling occurs. Three—your immune system determines which random outcomes fit the bill, filtering out the rest. Deterministically inducing a randomization process; being random; using predetermined criteria for filtering out the unuseful randomness. In the jargon of that field, this is “harnessing the stochasticity of hypermutation.” – Page 249

But where does that filter, reflecting your values, ethics, and character, come from? It’s chapter 3. And where does intent come from? How is it that one person’s filter filters out every random possibility other than “Rob the bank,” while another’s goes for “Wish the bank teller a good day”? And where do the values and criteria come from in even first deciding whether some circumstance merits activating Dennett’s random consideration generator? – Page 251

As discussed in the last chapter, downward causation is perfectly valid; the metaphor often used is that when a wheel is rolling, its high-level wheel-ness is causing its constituent parts to do forward rolls. And when you choose to pull a trigger, all of your index finger’s cells, organelles, molecules, atoms, and quarks move about an inch. – Page 252

And Some Conclusions About The Last Six Chapters

Reductionism is great. It’s a whole lot better to take on a pandemic by sequencing the gene for a viral coat protein than by trying to appease a vengeful deity with sacrificial offerings of goat intestines. Nonetheless, it has its limits, and what the revolutions of chaoticism, emergent complexity, and quantum indeterminism show is that some of the most interesting things about us defy pure reductionism. – Page 256

But despite the moving power in these nonreductive revolutions, they aren’t mother’s milk that nurtures free will. Nonreductionism doesn’t mean that there are no component parts. Or that component parts work differently once there are lots of them, or that complex things can fly away untethered from their component parts. A system being unpredictable doesn’t mean that it is enchanted, and magical explanations for things aren’t really explanations. – Page 257

10.5. Interlude

And those influences are deep and subterranean, and our ignorance of the shaping forces beneath the surface leads us to fill in the vacuum with stories of agency. – Page 258

They all merge into one—evolution produces genes marked by the epigenetics of early environment, which produce proteins that, facilitated by hormones in a particular context, work in the brain to produce you. A seamless continuum leaving no cracks between the disciplines into which to slip some free will. – Page 258

We can’t successfully wish to not wish for what we wish for; – Page 259

Moreover, as the point of chapter 4, it’s biological turtles all the way down with respect to all of who we are, not just some parts. It’s not the case that while our natural attributes and aptitudes are made of sciencey stuff, our character, resilience, and backbone come packaged in a soul. – Page 259

we can’t will ourselves to have more willpower. – Page 259

Yes, all the interesting things in the world can be shot through with chaoticism, including a cell, an organ, an organism, a society. And as a result, there are really important things that can’t be predicted, that can never be predicted. But nonetheless, every step in the progression of a chaotic system is made of determinism, not whim. – Page 259

it can be very unsettling when a sentence doesn’t end in the way that you potato. Likewise when behavior is random. – Page 260

I recognize that I’m on the fringe here, fellow traveling with only a handful of scholars (e.g., Gregg Caruso, Sam Harris, Derk Pereboom, Peter Strawson). – Page 260

Will we ever get to the point where our behavior is entirely predictable, given the deterministic gears grinding underneath? Never—that’s one of the points of chaoticism. But the rate at which we are accruing new insights into those gears is boggling—nearly every fact in this book was discovered in the last fifty years, probably half in the last five. The Society for Neuroscience, the world’s premier professional organization for brain scientists, grew from five hundred founding members to twenty-five thousand in its first quarter century. In the time it has taken you to read this paragraph, two different scientists have discovered the function in the brain of some gene and are already squabbling about who did it first. – Page 261

“There, I just decided to pick up this pen—are you telling me that was completely out of my control?” I don’t have the data to prove it, but I think I can predict above the chance level which of any given pair of students will be the one who picks up the pen. It’s more likely to be the student who skipped lunch and is hungry. It’s more likely to be the male, if it is a mixed-sex pair. It is especially more likely if it is a heterosexual male and the female is someone he wants to impress. It’s more likely to be the extrovert. It’s more likely to be the student who got way too little sleep last night and it’s now late afternoon. Or whose circulating androgen levels are higher than typical for them (independent of their sex). It’s more likely to be the student who, over the months of the class, has decided that I’m an irritating blowhard, just like their father. Marching further back, it’s more likely to be the one of the pair who is from a wealthy family, rather than on a full scholarship, who is the umpteenth generation of their family to attend a prestigious university, rather than the first member of their immigrant family to finish high school. It’s more likely if they’re not a firstborn son. It’s more likely if their immigrant parents chose to come to the U.S. for economic gain as opposed to having fled their native land as refugees from persecution, more likely if their ancestry is from an individualist culture rather than a collectivist one. It’s the first half of this book, providing an answer to their question, “There, I just decided to pick up this pen—are you telling me that was completely out of my control?” Yes, I am. – Page 262

11. Will We Run Amok?

The notion of running amok has a certain appeal. Rampaging like a frenzied, headless chicken can let off steam. It’s often a way to meet new, interesting people, plus it can be pretty aerobic. Despite those clear pluses, I haven’t been seriously tempted to run amok very often. It seems kind of tiring and you get all sweaty. And I worry that I’ll just seem insufficiently committed to the venture and wind up looking silly. – Page 264

The traditional interpretation is one that deftly sidesteps free will—through no fault of their own, the person is believed to be possessed by an evil spirit and is not held accountable for their actions.[ 2] “Don’t blame me; I was possessed by Hantu Belian, the evil tiger spirit of the forest” is just a hop, skip, and a jump away from “Don’t blame me; we are just biological machines.” – Page 265

Hard Determinists Careening Through The Streets

when people believe less in free will, they put less intentionality and effort into their actions, monitor their errors less closely, and are less invested in the outcomes of a task.[ – Page 268

An Ideal Model System

Fascinating work by psychologist Ara Norenzayan of the University of British Columbia shows that such “moralizing gods” are relatively new cultural inventions. Hunter-gatherers, whose lifestyle has dominated 99 percent of human history, do not invent moralizing gods. Sure, their gods might demand a top-of-the-line sacrifice now and then, but they have no interest in whether humans are nice to each other. Everything about the evolution of cooperation and prosociality is facilitated by stable, transparent relationships built on familiarity and the potential for reciprocity; these are precisely the conditions that would make for moral constraint in small hunter-gatherer bands, obviating the need for some god eavesdropping. It was not until humans started living in larger communities that religions with moralizing gods started to pop up. As humans transitioned to villages, cities, and then protostates, for the first time, human sociality included frequent transient and anonymous encounters with strangers. Which generated the need to invent all-seeing eyes in the sky, the moralizing gods who dominate the world religions.[ – Page 271

Atheists Gone Wild

it is always about morality—the widespread belief that believing in a god is essential for morality, – Page 274

Even atheists associate atheism with norm violations, which is pretty pathetic; behold, the self-hating atheist.[*],[ – Page 274

Saying Versus Doing

A large percentage of the relevant literature is based on “self-reporting” rather than empirical data, and it turns out that religious people are more concerned than atheists with maintaining a moral reputation, arising from the more common personality trait of being concerned about being socially desirable.[ – Page 276

Old, Rich, Socialized Women Versus Young, Poor, Solitary Guys

the increased charitability and volunteering found in religious people is not a function of how often they pray but, instead, how often they attend their house of worship, and atheists who show the same degree of involvement in a close-knit community show the same degree of good-neighborliness (in a similar vein, controlling for involvement in a social community significantly lessens the difference in rates of depression among theists versus atheists). Once you control for sex, age, socioeconomic status, marital status, and sociality, most of the differences between theists and atheists disappear.[ 22] The relevance of this point to free-will issues is clear; the extent to which someone does or doesn’t believe in free will, and how readily that view can be altered experimentally, is probably closely related to variables about age, sex, education, and so on, and these might actually be more important predictors of running-amok-ness. – Page 277

When You’Re Primed To Be Good For Goodness’ Sake

while prosociality in religious people is boosted by religious primes, prosociality in atheists is boosted just as much by the right kinds of secular primes. “I’d better be good or else I’ll get into trouble” can certainly be primed by “alij” or “eocpli.” Prosociality in atheists is also prompted by loftier secular concepts, like “civic,” “duty,” “liberty,” and “equality.”[*],[ 25] In other words, reminders, including implicit ones, of one’s ethical stances, moral principles, and values bring forth the same degree of decency in theists and atheists. It’s just that the prosociality of the two groups is moored in different values and principles, and thus primed in different contexts. Obviously, then, what counts as moral behavior is crucial. – Page 278

if you’re trying to decide who is more likely to run amok with antisocial behaviors, atheists will look bad if the question is “How much of your money would you give to charity for the poor?” But if the question is “How much of your money would you pay in higher taxes for more social services for the poor?” you’ll reach a different conclusion.[ – Page 279

One Atheist At A Time Versus An Infestation Of Them

what sort of society would they construct, when everyone is freed from being nice due to the fear of God? A moral and humane one, and this conclusion is not based on a thought experiment. What I’m referring to are those ever reliably utopian Scandinavians. – Page 280

lower average rates of religiosity in a country predict lower levels of corruption, more tolerance of racial and ethnic minorities, higher literacy rates, lower rates of overall crime and of homicide, and less frequent warfare.[ 29] Correlative studies like these always have the major problem of not telling anything about cause or effect. – Page 281

Who Needs The Help?

religious prosociality is mostly about religious people being nice to people like themselves. It’s mostly in-group. In economic games, for example, the enhanced honesty of religious subjects extends only to other players described to them as coreligionists, something made more extreme by religious primes. Moreover, the greater charitability of religious people in studies is accounted for by their contributing more to coreligionists, and the bulk of the charitability of highly religious people in the real world consists of charity to their own group.[ – Page 282

Into The Valley Of The Indifferent